ABS 306

Code: ABS 306

Country: Khmer

Style: Angkor Wat

Date: 1000 - 1200

Dimensions in cm WxHxD: 8 x 9.8 x 6.5

Materials: Bronze

Ganesha

Affiliation: Deva

Mantra: (Om Ganesaya Namah)

Weapon: Parasu (Axe),

Pasa (Lasso),

Ankusa (Hook)

Consort: Buddhi (wisdom),

Riddhi (prosperity),

Siddhi (attainment)

Mount: mouse

Ganesha (Sanskrit: Gaṇesa; listen (help·info)), also spelled Ganesa or Ganesh, is one of the best-known and most worshipped deities in Hinduism. Although he is known by many attributes, Ganesha's elephant head makes him easy to identify. Ganesha is widely revered as the Remover of Obstacles and more generally as Lord of Beginnings and Lord of Obstacles (Vighnesha), patron of arts and sciences, and the deva of intellect and wisdom. He is honored with affection at the start of rituals and ceremonies and invoked as Patron of Letters during writing sessions. Several texts relate mythological anecdotes associated with his birth and exploits and explain his distinct iconography.

Ganesha emerged as a distinct deity in clearly-recognizable form in the fourth and fifth centuries, during the Gupta Period, although he inherited traits from Vedic and pre-Vedic precursors. His popularity rose quickly, and he was formally included among the five primary deities of Smartism (a Hindu denomination) in the ninth century. A sect of devotees called the Ganapatya, (Sanskrit: ganapatya), who identified Ganesha as the supreme deity, arose during this period. The principal scriptures dedicated to Ganesha are the Ganesha Purana, the Mudgala Purana, and the Ganapati Atharvashirsa.

Ganesha is one of the most-venerated divinities in India. Hindu sects worship him regardless of other affiliations. Devotion to Ganesha is widely diffused and extends to Jains, Buddhists, and beyond India.

Etymology and other names

Ganesha has many other titles and epithets, including Ganapati and Vighnesvara. The Hindu title of respect Shri (Sanskrit: sri, also spelled Sri or Shree) is often added before his name. One popular way Ganesha is worshipped is by chanting a Ganesha Sahasranama, a litany of "a thousand names of Ganesha". Each name in the sahasranama conveys a different meaning and symbolises a different aspect of Ganesha. At least two different versions of the Ganesha Sahasranama exist. One of these is drawn from the Ganesha Purana, a Hindu scripture that venerates Ganesha.

The name Ganesha is a Sanskrit compound, joining the words gana (Sanskrit: gana), meaning a group, multitude, or categorical system and isha (Sanskrit: tsa), meaning lord or master. The word gana when associated with Ganesha is often taken to refer to the ganas, a troop of semi-divine beings that form part of the retinue of Shiva.The term more generally means a category, class, community, association, or corporation. Some commentators interpret the name "Lord of the Ganas" to mean "Lord of created categories," or "Lord of Hosts" such as the elements. Ganapati (Sanskrit: ganapati), a synonym for Ganesha, is a compound composed of gana, meaning "group", and pati, meaning "ruler" or "lord".The Amarakosa, an early Sanskrit lexicon, lists eight synonyms of Ganesa : Vinayaka, Vighnaraja (equivalent to Vighnesa), Dvaimatura (one who has two mothers),Ganadhipa (equivalent to Gaṇapati and Ganesa), Ekadanta (one who has one tusk), Heramba, Lambodara (one who has a pot belly, or, literally, one who has a hanging belly) and Gajanana (having the face of an elephant).

Vinayaka is a common name for Ganesha that appears in the Puranas and in Buddhist Tantras. This name is reflected in the naming of the eight famous Ganesha temples in Maharashtra known as the astavinayaka. The name Vignesha (Lord of Obstacles) refers to his primary function in Hindu mythology as the creator and remover of obstacles (vighna).

A prominent name for Ganesha in the Tamil language is Pille or Pillaiyar (Little Child). A. K. Narain differentiates these terms by saying that pille means a "child" while pillaiyar means a "noble child". He adds that the words pallu, pella, and pell in the Dravidian family of languages signify "tooth or tusk of an elephant" but more generally "elephant". In discussing the name Pillaiyar, Anita Raina Thapan notes that since the Pali word pillaka means "a young elephant" it is possible that the word pille originally meant "the young of the elephant".

Iconography

Ganesha is a popular figure in Indian art. Unlike those of some deities, representations of Ganesha show wide variation with distinct patterns changing over time. He may be portrayed standing, dancing, heroically taking action against demons, playing with his family as a boy, sitting down, or engaging in a range of contemporary situations.

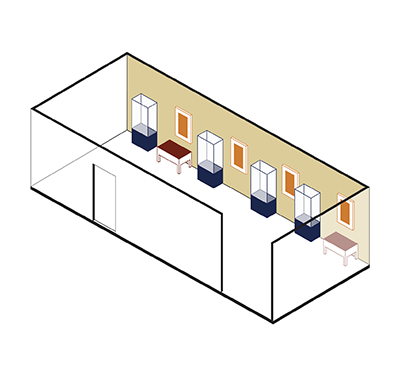

Ganesha images were prevalent in many parts of India by the sixth century. The figure shown to the right is typical of Ganesha statuary from 900–1200, after Ganesha had been well-established as an independent deity with his own sect. This example features some of Ganesha's common iconographic elements. A virtually identical statue has been dated between 973–1200 by Paul Martin-Dubost, and another similar statue is dated circa twelfth century by Pratapaditya Pal. Ganesha has the head of an elephant and a big belly. This statue has four arms, which is common in depictions of Ganesha. He holds his own broken tusk in his lower-right hand and holds a delicacy, which he samples with his trunk, in his lower-left hand. The motif of Ganesha turning his trunk sharply to his left to taste a sweet in his lower-left hand is a particularly archaic feature. A more primitive statue in one of the Ellora Caves with this general form has been dated to the seventh century. Details of the other hands are difficult to make out on the statue shown; in the standard configuration, Ganesha typically holds an axe or a goad in one upper arm and a noose in the other upper arm as symbols of his ability to cut through obstacles or to create them as needed.

The influence of this old constellation of iconographic elements can still be seen in contemporary representations of Ganesha. In one modern form, the only variation from these old elements is that the lower-right hand does not hold the broken tusk but rather is turned toward the viewer in a gesture of protection or fearlessness (abhaya mudra). The same combination of four arms and attributes occurs in statues of Ganesha dancing, which is a very popular theme.

Common attributes

Ganesha has been represented with the head of an elephant since the early stages of his appearance in Indian art. Puranic myths provide many explanations for how he got his elephant head. One of his popular forms, Heramba-Ganapati, has five elephant heads, and other less-common variations in the number of heads are known. While some texts say that Ganesha was born with an elephant head, in most stories he acquires the head later. The most common motif in these stories is that Ganesha was born with a human head and body and that Shiva beheaded him when Ganesha came between Shiva and Parvati. Shiva then replaced Ganesha's original head with that of an elephant. Details of the battle and where the replacement head came from vary according to different sources. In another story, when Ganesha was born, his mother, Parvati, showed off her new baby to the other gods. Unfortunately, the god Shani (Saturn), who is said to have the evil eye, looked at him, causing the baby's head to be burned to ashes. The god Vishnu came to the rescue and replaced the missing head with that of an elephant. Another story says that Ganesha was created directly by Shiva's laughter. Because Shiva considered Ganesha too alluring, he gave him the head of an elephant and a protruding belly.

Ganesha's earliest name was Ekadanta (One Tusk), referring to his single whole tusk, the other having been broken off. Some of the earliest images of Ganesha show him holding his broken tusk. The importance of this distinctive feature is reflected in the Mudgala Purana, which states that the name of Ganesha's second incarnation is Ekadanta. Ganesha's protruding belly appears as a distinctive attribute in his earliest statuary, which dates to the Gupta period (fourth to sixth centuries). This feature is so important that according to the Mudgala Purana two different incarnations of Ganesha use names, Lambodara (Pot Belly, or, literally, Hanging Belly) and Mahodara (Great Belly), based on it. Both names are Sanskrit compounds describing his belly (Sanskrit: udara). The Brahmanda Purana says that he has the name Lambodara because all the universes (i.e., cosmic eggs; Sanskrit brahmandas) of the past, present, and future are present in Ganesha. The number of Ganesha's arms varies; his best-known forms have between two and sixteen arms. Many depictions of Ganesha feature four arms, which is mentioned in Puranic sources and codified as a standard form in some iconographic texts. His earliest images had two arms. Forms with fourteen and twenty arms appeared in Central India during the ninth and tenth centuries. The serpent is a common feature in Ganesha iconography and appears in many forms. According to the Ganesha Purana, Ganesha wrapped the serpent Vāsuki around his neck. Other common depictions of snakes include use as a sacred thread (Sanskrit: yajnyopavita) wrapped around the stomach as a belt, held in a hand, coiled at the ankles, or as a throne. Upon Ganesha's forehead there may be a third eye or the Shaivite sectarian mark (Sanskrit: tilaka), three horizontal lines. The Ganesha Purana prescribes a tilaka mark as well as a crescent moon on the forehead. A distinct form called Bhalacandra (Moon on the Forehead) includes that iconographic element.

The colors most often associated with Ganesha are red and yellow, but specific other colors are associated with certain forms. Many examples of color associations with specific meditation forms are prescribed in the Sritattvanidhi, which is a treatise on Hindu iconography that includes a section on variant forms of Ganesha. For example, white is associated with his representations as Heramba-Ganapati and Rina-Mochana-Ganapati (Ganapati Who Releases from Bondage). Ekadanta-Ganapati is visualized as blue during meditation on that form.

Vahanas of Ganesha

The earliest Ganesha images are without a Vahana (mount). Of the eight incarnations of Ganesha described in the Mudgala Purana, Ganesha has a mouse in five of them, uses a lion in his incarnation as Vakratunda, a peacock in his incarnation of Vikata, and Shesha, the divine serpent, in his incarnation as Vighnaraja.Of the four incarnations of Ganesha listed in the Ganesha Purana, Mohotkata has a lion, Mayuresvara has a peacock, Dhumraketu has a horse, and Gajanana has a rat. Jain depictions of Ganesha show his vahana variously as a mouse, an elephant, a tortoise, a ram, or a peacock.

Mouse or rat as vahana

Ganesha is often shown riding on or attended by a mouse or rat. Martin-Dubost says that in central and western India the rat began to appear as the principal vehicle in sculptures of Ganesa in the seventh century CE, when the rat was always placed close to his feet. The mouse as a mount first appears in written sources in the Matsya Purana and later in the Brahmananda Purana and Ganesha Purana, where Ganesha uses it as his vehicle only in his last incarnation. The Ganapati Atharvashirsa includes a meditation verse on Ganesha that describes the mouse appearing on his flag. The names Musakavahana (mouse-mount) and Akhuketana (rat-banner) appear in the Ganesha Sahasranama.

The mouse is interpreted in several ways. According to Grimes, "Many, if not most of those who interpret Gaṇapati's mouse, do so negatively; it symbolizes tamoguna as well as desire". Along these lines, Michael Wilcockson says it symbolizes those who wish to overcome desires and be less selfish. Krishan notes that the rat is destructive and a menace to crops. The Sanskrit word musaka (mouse) is derived from the root mus (stealing, robbing). It was essential to subdue the rat as a destructive pest, a type of vighna (impediment) that needed to be overcome. According to this theory, showing Ganesha as master of the rat demonstrates his function as Vigneshvara and gives evidence of his possible role as a folk gramata-devata (village deity) who later rose to greater prominence. Martin-Dubost notes a view that the rat is a symbol suggesting that Ganesha, like the rat, penetrates even the most secret places.

Obstacles

Ganesha is Vighnesvara or Vighnaraja, the Lord of Obstacles, both of a material and spiritual order. He is popularly worshipped as a remover of obstacles although traditionally he also places obstacles in the path of those who need to be checked. Paul Courtright says that: "His task in the divine scheme of things, his dharma, is to place and remove obstacles. It is his particular territory, the reason for his creation."

Krishan notes that some of his names reflect shadings of multiple roles that have evolved over time. Dhavalikar ascribes the quick ascension of Ganesha in the Hindu pantheon, and the emergence of the Ganapatyas, to this shift in emphasis from vighnakarta (obstacle-creator) to vighnaharta (obstacle-averter). Both functions however continue to be vital to his character, as Robert Brown explains: "Even after the Puranic Ganesa is well-defined, in art Ganesa remained predominantly important for his dual role as creator and remover of obstacles, thus having both a negative and a positive aspect".

Buddhi

Ganesha is considered to be the Lord of Intelligence. In Sanskrit, the word buddhi is a feminine noun that is variously translated as intelligence, wisdom, or intellect. The concept of buddhi is closely associated with the personality of Ganesha, especially in the Puranic period, when many stories stress his cleverness and love of intelligence. One of Ganesha's names in the Ganesha Purana and the Ganesha Sahasranama is Buddhipriya. This name also appears in a list of twenty-one names that Ganesa, at the end of the Ganesha Sahasranama, says are especially important. The word priya can mean "fond of," and in a marital context it can mean "lover" or "husband," so the name may mean either Fond of Intelligence or Buddhi's Husband.

Aum

Ganesha is identified with the Hindu mantra Aum (also called Om). The term omkarasvarupa (Aum is his form), when identified with Ganesha, refers to the notion that he personifies the primal sound. The Ganapati Atharvashirsa attests to this association. Chinmayananda translates the relevant passage as follows:

(O Lord Ganapati!) You are (the Trinity) Brahma, Vishnu, and Mahesa. You are Indra. You are fire [Agni] and air [Vayu]. You are the sun [Surya] and the moon [Candrama]. You are Brahman. You are (the three worlds) Bhuloka [earth], Antariksha-loka [space], and Swargaloka [heaven]. You are Om. (That is to say, You are all this).

Some devotees see similarities between the shape of his body in iconography and the shape of Om in the Devanāgarīand Tamil scripts.

First chakra

As attested to in the Ganapati Atharvashirsa, Ganesha is associated with the first or root chakra (muladhara). Courtright translates this passage as follows:

You continually dwell in the sacral plexus at the base of the spine [muladhara cakra].

Family and consorts

Though Ganesha is popularly held to be the son of Shiva and Parvati, the Puranic myths disagree about his birth. He may be said to be created by Shiva, or by Parvati, or by Shiva and Parvati, or to appear mysteriously and then to be discovered by Shiva and Parvati.

The family includes his brother Skanda, who is also called Karttikeya, Murugan, and other names. Regional differences dictate the order of their births. In northern India, Skanda is generally said to be the elder, while in the south, Ganesha is considered the first born. Skanda was an important martial deity from about 500 BCE to about 600 CE, when worship of him declined significantly in northern India. As Skanda fell, Ganesha rose. Several stories tell of sibling rivalry between the brothers and may reflect sectarian tensions.

Ganesha's marital status, the subject of considerable scholarly review, varies widely in mythological stories. One pattern of myths identifies Ganesha as an unmarried brahmacarin. This view is common in southern India and parts of northern India. Another pattern associates him with the concepts of Buddhi (intellect), Siddhi (spiritual power), and Riddhi (prosperity); these qualities are sometimes personified as goddesses, said to be Ganesha's wives. He also may be shown with a single consort or a nameless servant (Sanskrit: dasi). Another pattern connects Ganesha with the goddess of culture and the arts, Sarasvati or Sarda (particularly in Maharashtra). He is also associated with the goddess of luck and prosperity, Lakshmi. Another pattern, mainly prevalent in the Bengal region, links Ganesha with the banana tree, Kala Bo.

The Shiva Purana says that Ganesha had two sons: Ksema (prosperity) and Labha (profit). In Northern Indian variants of this story, the sons are often said to be Subha (auspiciouness) and Labha. The 1975 Hindi film Jai Santoshi Maa shows Ganesha married to Riddhi and Siddhi and having a daughter named Santoshi Ma, the goddess of satisfaction. This story has no Puranic basis, and Anita Raina Thapan and Lawrence Cohen cite Santoshi Ma's cult as evidence of Ganesha's continuing evolution as a popular deity.

First appearance

Ganesha appeared in his classic form as a clearly-recognizable deity with well-defined iconographic attributes in the early fourth to fifth centuries. Shanti Lal Nagar says that the earliest known cult image of Ganesha is in the niche of the Shiva temple at Bhumra, which has been dated to the Gupta period. His independent cult appeared by about the tenth century. Narain sums up controversy between devotees and academics regarding the development of Ganesha as follows:

What is inscrutable is the somewhat dramatic appearance of Ganesa on the historical scene. His antecedents are not clear. His wide acceptance and popularity, which transcend sectarian and territorial limits, are indeed amazing. On the one hand there is the pious belief of the orthodox devotees in Ganesa's Vedic origins and in the Puranic explanations contained in the confusing, but nonetheless interesting, mythology. On the other hand, there are doubts about the existence of the idea and the icon of this deity" before the fourth to fifth century A.D. ... [I]n my opinion, indeed there is no convincing evidence of the existence of this divinity prior to the fifth century.

Possible influences

Courtright reviews various speculative theories about the early history of Ganesha, including supposed tribal traditions and animal cults, and dismisses all of them in this way:

In this search for a historical origin for Ganesa, some have suggested precise locations outside the Brahmanic tradition.... These historical locations are intriguing to be sure, but the fact remains that they are all speculations, variations on the Dravidian hypothesis, which argues that anything not attested to in the Vedic and Indo-European sources must have come into Brahmanic religion from the Dravidian or aboriginal populations of India as part of the process that produced Hinduism out of the interactions of the Aryan and non-Aryan populations. There is no independent evidence for an elephant cult or a totem; nor is there any archaeological data pointing to a tradition prior to what we can already see in place in the Puranic literature and the iconography of Ganesa.

Thapan's book on the development of Ganesha devotes a chapter to speculations about the role elephants had in early India but concludes that:

Although by the second century AD the elephant-headed yaksa form exists it cannot be presumed to represent Ganapati-Vinayaka. There is no evidence of a deity by this name having an elephant or elephant-headed form at this early stage. Ganapati-Vinayaka had yet to make his debut.

One theory of the origin of Ganesha is that he gradually came to prominence in connection with the four Vinayakas. In Hindu mythology the Vinayakas were a group of four troublesome demons who created obstacles and difficulties but who were easily propitiated. The name Vinayaka is a common name for Ganesha both in the Puranas and in Buddhist Tantras. Krishan is one of the academics who accepts this view, stating flatly of Ganesha, "He is a non-vedic god. His origin is to be traced to the four Vina yakas, evil spirits, of the Manavagrhyasutra (7th–4th century B.C.) who cause various types of evil and suffering".

Depictions of elephant-headed human figures, which some identify with Ganesha, appear in Indian art and coinage as early as the second century BCE.

The title "Leader of the group" (Sanskrit: gaṇapati) occurs twice in the Rig Veda, but in neither case does it refer to the modern Ganesha. The term appears in RV 2.23.1 as a title for Brahmanaspati according to commentators. While this verse doubtless refers to Brahmanaspati, it was later adopted for worship of Ganesha and is still used today. In rejecting any claim that this passage is evidence of Ganesha in the Rig Veda, Ludo Rocher says that it "clearly refers to Brhaspati—who is the deity of the hymn—and Brhaspati only". Equally clearly, the second passage (RV 10.112.9) refers to Indra, who is given the epithet 'gaṇapati', translated "Lord of the companies (of the Maruts)."However, Roucher notes that the more recent Ganapatya literature often quotes the Rigvedic verses to accord Ganesha Vedic respectability.

Two verses in texts belonging to Black Yajurveda, Maitrayaniya Samhita (2.9.1) and Taittiriya Aranyaka (10.1), appeal to a deity as "the tusked one" (Dantih), "elephant-faced" (Hastimukha), and "with a curved trunk" (Vakratunda). These names are suggestive of Ganesha, and the 14th century commentator Sayana explicitly establishes this identification. The description of Dantin, possessing a twisted trunk (vakratunda) and holding a corn-sheaf, a sugar cane, and a club, is so characteristic of the Puranic Ganapati that Heras says, "we cannot resist to accept his full identification with this Vedic Dantin". However, Krishan considers these hymns to be post-Vedic additions. Thapan reports that these passages are "generally considered to have been interpolated", and Dhavalikar says, "the references to the elephant-headed deity in the Maitrayani Samhita have been proven to be very late interpolations, and thus are not very helpful for determining the early formation of the deity".

Ganesha does not appear in Indian epic literature that is dated to the Vedic period. A late interpolation to the epic poem Mahabharata says that the sage Vyasa asked Ganesha to serve as his scribe to transcribe the poem as he dictated it to him. Ganesha agreed but only on condition that Vyasa recite the poem uninterrupted, that is, without pausing. The sage agreed to this but found that to get any rest he needed to recite very complex passages so Ganesha would have to ask for clarifications. The story is not accepted as part of the original text by the editors of the critical edition of the Mahabharata, in which the twenty-line story is relegated to a footnote in an appendix. The story of Ganesha acting as the scribe occurs in 37 of the 59 manuscripts consulted during preparation of the critical edition. Ganesha's association with mental agility and learning is one reason he is shown as scribe for Vyasa's dictation of the Mahabharata in this interpolation. Richard L. Brown dates the story to the eighth century, and Moriz Winternitz concludes that it was known as early as c. 900, but it had not yet been added to the Mahabharata some 150 years later. Winternitz also notes that a distinctive feature in South Indian manuscripts of the Mahabharata is their omission of this Ganesha legend. The term vinayaka is found in some recensions of the Santiparva and Anusasanaparva that are regarded as interpolations. A reference to Vighnakartrinam ("Creator of Obstacles") in Vanaparva is also believed to be an interpolation and does not appear in the critical edition.

Puranic period

Stories about Ganesha often occur in the Puranic corpus. Brown notes while the Puranas "defy precise chronological ordering", the more detailed narratives of Ganesha's life are in the late texts, circa 600–1300. Yuvraj Krishan says that the Puranic myths about the birth of Ganesha and how he acquired an elephant's head are in the later Puranas composed from about 600 onwards and that references to Ganesha in the earlier Puranas such as the Vayu and Brahmanda Puranas are later interpolations made during the seventh to tenth centuries.

In his survey of Ganesha's rise to prominence in Sanskrit literature, Ludo Rocher notes that:

Above all, one cannot help being struck by the fact that the numerous stories surrounding Gaṇeśa concentrate on an unexpectedly limited number of incidents. These incidents are mainly three: his birth and parenthood, his elephant head, and his single tusk. Other incidents are touched on in the texts, but to a far lesser extent.

Ganesha's rise to prominence was codified in the ninth century when he was formally included as one of the five primary deities of Smartism. The ninth-century philosopher Sankaracarya popularized the "worship of the five forms" (pancayatana puja) system among orthodox Brahmins of the Smarta tradition. This worship practice invokes the five deities Ganesha, Vishnu, Shiva, Devi, and Surya. Sankaracarya instituted the tradition primarily to unite the principal deities of these five major sects on an equal status. This formalized the role of Ganesha as a complementary deity.

Beyond India and Hinduism

India had an impact on the regions of western and southeast Asia as a result of commercial and cultural contacts. Ganesha is one of many Hindu deities who reached foreign lands as a result. The worship of Ganesha by Hindus outside of India shows regional variation.

Ganesha was particularly worshipped by traders and merchants, who went out of India for commercial ventures. The period from approximately the tenth century onwards was marked by the development of new networks of exchange, the formation of trade guilds, and a resurgence of money circulation. During this time, Ganesha became the principal deity associated with traders. The earliest inscription invoking Ganesha before any other deity is associated with the merchant community.

Hindus migrated to the Malay Archipelago and took their culture, including Ganesha, with them. Statues of Ganesha are found throughout the Malay Archipelago in great numbers, often beside Shiva sanctuaries. The forms of Ganesha found in Hindu art of Java, Bali, and Borneo show specific regional influences. The gradual spread of Hindu culture to south east Asia established Ganesha in modified forms in Burma, Cambodia, and Thailand. In Indochina, Hinduism and Buddhism were practiced side-by-side, and mutual influences can be seen in the iconography of Ganesha in the region. In Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam, Ganesha was mainly thought of as a remover of obstacles. Even today in Buddhist Thailand, Ganesha is regarded as a remover of obstacles, the god of success.

Before the arrival of Islam, Afghanistan had close cultural ties with India, and the adoration of both Hindu and Buddhist deities was practiced. A few examples of sculptures from the fifth to the seventh centuries have survived, suggesting that the worship of Ganesha was then in vogue in the region.

Ganesha appears in Mahayana Buddhism, not only in the form of the Buddhist god Vinayaka, but also as a Hindu demon form with the same name (Vinayaka).His image appears in Buddhist sculptures during the late Gupta period. As the Buddhist god Vinayaka, he is often shown dancing, a form called Nrtta Ganapati that was popular in northern India, later adopted in Nepal and then in Tibet. In Nepal, the Hindu form of Ganesha known as Heramba is very popular, where he appears with five heads and rides a lion. Tibetan representations of Ganesha show ambivalent views of him. A Tibetan rendering of Ganapati is tshogs bdag. In one Tibetan form, he is shown being trodden under foot by Mahakala, a popular Tibetan deity. Other depictions show him as the Destroyer of Obstacles, sometimes dancing. Ganesha appears in China and Japan in forms that show distinct regional character. In northern China, the earliest known stone statue of Ganesha carries an inscription dated 531 CE. In Japan the Ganesha cult was first mentioned in 806 CE.

The canonical literature of Jainism does not mention the cult of Ganesha. However Ganesha is worshipped by most Jains, for whom he appears to have taken over certain functions of Kubera. Jain connections with the trading community support the idea that Jainism took up Ganesha worship as a result of commercial connections. The earliest known Jain Ganesha statue dates to about the ninth century. A fifteenth century Jain text lists procedures for the installation of Ganapati images. Images of Ganesha appear in the Jain temples of Rajasthan and Gujarat.

Affiliation: Deva

Mantra: (Om Ganesaya Namah)

Weapon: Parasu (Axe),

Pasa (Lasso),

Ankusa (Hook)

Consort: Buddhi (wisdom),

Riddhi (prosperity),

Siddhi (attainment)

Mount: mouse

Ganesha (Sanskrit: Gaṇesa; listen (help·info)), also spelled Ganesa or Ganesh, is one of the best-known and most worshipped deities in Hinduism. Although he is known by many attributes, Ganesha's elephant head makes him easy to identify. Ganesha is widely revered as the Remover of Obstacles and more generally as Lord of Beginnings and Lord of Obstacles (Vighnesha), patron of arts and sciences, and the deva of intellect and wisdom. He is honored with affection at the start of rituals and ceremonies and invoked as Patron of Letters during writing sessions. Several texts relate mythological anecdotes associated with his birth and exploits and explain his distinct iconography.

Ganesha emerged as a distinct deity in clearly-recognizable form in the fourth and fifth centuries, during the Gupta Period, although he inherited traits from Vedic and pre-Vedic precursors. His popularity rose quickly, and he was formally included among the five primary deities of Smartism (a Hindu denomination) in the ninth century. A sect of devotees called the Ganapatya, (Sanskrit: ganapatya), who identified Ganesha as the supreme deity, arose during this period. The principal scriptures dedicated to Ganesha are the Ganesha Purana, the Mudgala Purana, and the Ganapati Atharvashirsa.

Ganesha is one of the most-venerated divinities in India. Hindu sects worship him regardless of other affiliations. Devotion to Ganesha is widely diffused and extends to Jains, Buddhists, and beyond India.

Etymology and other names

Ganesha has many other titles and epithets, including Ganapati and Vighnesvara. The Hindu title of respect Shri (Sanskrit: sri, also spelled Sri or Shree) is often added before his name. One popular way Ganesha is worshipped is by chanting a Ganesha Sahasranama, a litany of "a thousand names of Ganesha". Each name in the sahasranama conveys a different meaning and symbolises a different aspect of Ganesha. At least two different versions of the Ganesha Sahasranama exist. One of these is drawn from the Ganesha Purana, a Hindu scripture that venerates Ganesha.

The name Ganesha is a Sanskrit compound, joining the words gana (Sanskrit: gana), meaning a group, multitude, or categorical system and isha (Sanskrit: tsa), meaning lord or master. The word gana when associated with Ganesha is often taken to refer to the ganas, a troop of semi-divine beings that form part of the retinue of Shiva.The term more generally means a category, class, community, association, or corporation. Some commentators interpret the name "Lord of the Ganas" to mean "Lord of created categories," or "Lord of Hosts" such as the elements. Ganapati (Sanskrit: ganapati), a synonym for Ganesha, is a compound composed of gana, meaning "group", and pati, meaning "ruler" or "lord".The Amarakosa, an early Sanskrit lexicon, lists eight synonyms of Ganesa : Vinayaka, Vighnaraja (equivalent to Vighnesa), Dvaimatura (one who has two mothers),Ganadhipa (equivalent to Gaṇapati and Ganesa), Ekadanta (one who has one tusk), Heramba, Lambodara (one who has a pot belly, or, literally, one who has a hanging belly) and Gajanana (having the face of an elephant).

Vinayaka is a common name for Ganesha that appears in the Puranas and in Buddhist Tantras. This name is reflected in the naming of the eight famous Ganesha temples in Maharashtra known as the astavinayaka. The name Vignesha (Lord of Obstacles) refers to his primary function in Hindu mythology as the creator and remover of obstacles (vighna).

A prominent name for Ganesha in the Tamil language is Pille or Pillaiyar (Little Child). A. K. Narain differentiates these terms by saying that pille means a "child" while pillaiyar means a "noble child". He adds that the words pallu, pella, and pell in the Dravidian family of languages signify "tooth or tusk of an elephant" but more generally "elephant". In discussing the name Pillaiyar, Anita Raina Thapan notes that since the Pali word pillaka means "a young elephant" it is possible that the word pille originally meant "the young of the elephant".

Iconography

Ganesha is a popular figure in Indian art. Unlike those of some deities, representations of Ganesha show wide variation with distinct patterns changing over time. He may be portrayed standing, dancing, heroically taking action against demons, playing with his family as a boy, sitting down, or engaging in a range of contemporary situations.

Ganesha images were prevalent in many parts of India by the sixth century. The figure shown to the right is typical of Ganesha statuary from 900–1200, after Ganesha had been well-established as an independent deity with his own sect. This example features some of Ganesha's common iconographic elements. A virtually identical statue has been dated between 973–1200 by Paul Martin-Dubost, and another similar statue is dated circa twelfth century by Pratapaditya Pal. Ganesha has the head of an elephant and a big belly. This statue has four arms, which is common in depictions of Ganesha. He holds his own broken tusk in his lower-right hand and holds a delicacy, which he samples with his trunk, in his lower-left hand. The motif of Ganesha turning his trunk sharply to his left to taste a sweet in his lower-left hand is a particularly archaic feature. A more primitive statue in one of the Ellora Caves with this general form has been dated to the seventh century. Details of the other hands are difficult to make out on the statue shown; in the standard configuration, Ganesha typically holds an axe or a goad in one upper arm and a noose in the other upper arm as symbols of his ability to cut through obstacles or to create them as needed.

The influence of this old constellation of iconographic elements can still be seen in contemporary representations of Ganesha. In one modern form, the only variation from these old elements is that the lower-right hand does not hold the broken tusk but rather is turned toward the viewer in a gesture of protection or fearlessness (abhaya mudra). The same combination of four arms and attributes occurs in statues of Ganesha dancing, which is a very popular theme.

Common attributes

Ganesha has been represented with the head of an elephant since the early stages of his appearance in Indian art. Puranic myths provide many explanations for how he got his elephant head. One of his popular forms, Heramba-Ganapati, has five elephant heads, and other less-common variations in the number of heads are known. While some texts say that Ganesha was born with an elephant head, in most stories he acquires the head later. The most common motif in these stories is that Ganesha was born with a human head and body and that Shiva beheaded him when Ganesha came between Shiva and Parvati. Shiva then replaced Ganesha's original head with that of an elephant. Details of the battle and where the replacement head came from vary according to different sources. In another story, when Ganesha was born, his mother, Parvati, showed off her new baby to the other gods. Unfortunately, the god Shani (Saturn), who is said to have the evil eye, looked at him, causing the baby's head to be burned to ashes. The god Vishnu came to the rescue and replaced the missing head with that of an elephant. Another story says that Ganesha was created directly by Shiva's laughter. Because Shiva considered Ganesha too alluring, he gave him the head of an elephant and a protruding belly.

Ganesha's earliest name was Ekadanta (One Tusk), referring to his single whole tusk, the other having been broken off. Some of the earliest images of Ganesha show him holding his broken tusk. The importance of this distinctive feature is reflected in the Mudgala Purana, which states that the name of Ganesha's second incarnation is Ekadanta. Ganesha's protruding belly appears as a distinctive attribute in his earliest statuary, which dates to the Gupta period (fourth to sixth centuries). This feature is so important that according to the Mudgala Purana two different incarnations of Ganesha use names, Lambodara (Pot Belly, or, literally, Hanging Belly) and Mahodara (Great Belly), based on it. Both names are Sanskrit compounds describing his belly (Sanskrit: udara). The Brahmanda Purana says that he has the name Lambodara because all the universes (i.e., cosmic eggs; Sanskrit brahmandas) of the past, present, and future are present in Ganesha. The number of Ganesha's arms varies; his best-known forms have between two and sixteen arms. Many depictions of Ganesha feature four arms, which is mentioned in Puranic sources and codified as a standard form in some iconographic texts. His earliest images had two arms. Forms with fourteen and twenty arms appeared in Central India during the ninth and tenth centuries. The serpent is a common feature in Ganesha iconography and appears in many forms. According to the Ganesha Purana, Ganesha wrapped the serpent Vāsuki around his neck. Other common depictions of snakes include use as a sacred thread (Sanskrit: yajnyopavita) wrapped around the stomach as a belt, held in a hand, coiled at the ankles, or as a throne. Upon Ganesha's forehead there may be a third eye or the Shaivite sectarian mark (Sanskrit: tilaka), three horizontal lines. The Ganesha Purana prescribes a tilaka mark as well as a crescent moon on the forehead. A distinct form called Bhalacandra (Moon on the Forehead) includes that iconographic element.

The colors most often associated with Ganesha are red and yellow, but specific other colors are associated with certain forms. Many examples of color associations with specific meditation forms are prescribed in the Sritattvanidhi, which is a treatise on Hindu iconography that includes a section on variant forms of Ganesha. For example, white is associated with his representations as Heramba-Ganapati and Rina-Mochana-Ganapati (Ganapati Who Releases from Bondage). Ekadanta-Ganapati is visualized as blue during meditation on that form.

Vahanas of Ganesha

The earliest Ganesha images are without a Vahana (mount). Of the eight incarnations of Ganesha described in the Mudgala Purana, Ganesha has a mouse in five of them, uses a lion in his incarnation as Vakratunda, a peacock in his incarnation of Vikata, and Shesha, the divine serpent, in his incarnation as Vighnaraja.Of the four incarnations of Ganesha listed in the Ganesha Purana, Mohotkata has a lion, Mayuresvara has a peacock, Dhumraketu has a horse, and Gajanana has a rat. Jain depictions of Ganesha show his vahana variously as a mouse, an elephant, a tortoise, a ram, or a peacock.

Mouse or rat as vahana

Ganesha is often shown riding on or attended by a mouse or rat. Martin-Dubost says that in central and western India the rat began to appear as the principal vehicle in sculptures of Ganesa in the seventh century CE, when the rat was always placed close to his feet. The mouse as a mount first appears in written sources in the Matsya Purana and later in the Brahmananda Purana and Ganesha Purana, where Ganesha uses it as his vehicle only in his last incarnation. The Ganapati Atharvashirsa includes a meditation verse on Ganesha that describes the mouse appearing on his flag. The names Musakavahana (mouse-mount) and Akhuketana (rat-banner) appear in the Ganesha Sahasranama.

The mouse is interpreted in several ways. According to Grimes, "Many, if not most of those who interpret Gaṇapati's mouse, do so negatively; it symbolizes tamoguna as well as desire". Along these lines, Michael Wilcockson says it symbolizes those who wish to overcome desires and be less selfish. Krishan notes that the rat is destructive and a menace to crops. The Sanskrit word musaka (mouse) is derived from the root mus (stealing, robbing). It was essential to subdue the rat as a destructive pest, a type of vighna (impediment) that needed to be overcome. According to this theory, showing Ganesha as master of the rat demonstrates his function as Vigneshvara and gives evidence of his possible role as a folk gramata-devata (village deity) who later rose to greater prominence. Martin-Dubost notes a view that the rat is a symbol suggesting that Ganesha, like the rat, penetrates even the most secret places.

Obstacles

Ganesha is Vighnesvara or Vighnaraja, the Lord of Obstacles, both of a material and spiritual order. He is popularly worshipped as a remover of obstacles although traditionally he also places obstacles in the path of those who need to be checked. Paul Courtright says that: "His task in the divine scheme of things, his dharma, is to place and remove obstacles. It is his particular territory, the reason for his creation."

Krishan notes that some of his names reflect shadings of multiple roles that have evolved over time. Dhavalikar ascribes the quick ascension of Ganesha in the Hindu pantheon, and the emergence of the Ganapatyas, to this shift in emphasis from vighnakarta (obstacle-creator) to vighnaharta (obstacle-averter). Both functions however continue to be vital to his character, as Robert Brown explains: "Even after the Puranic Ganesa is well-defined, in art Ganesa remained predominantly important for his dual role as creator and remover of obstacles, thus having both a negative and a positive aspect".

Buddhi

Ganesha is considered to be the Lord of Intelligence. In Sanskrit, the word buddhi is a feminine noun that is variously translated as intelligence, wisdom, or intellect. The concept of buddhi is closely associated with the personality of Ganesha, especially in the Puranic period, when many stories stress his cleverness and love of intelligence. One of Ganesha's names in the Ganesha Purana and the Ganesha Sahasranama is Buddhipriya. This name also appears in a list of twenty-one names that Ganesa, at the end of the Ganesha Sahasranama, says are especially important. The word priya can mean "fond of," and in a marital context it can mean "lover" or "husband," so the name may mean either Fond of Intelligence or Buddhi's Husband.

Aum

Ganesha is identified with the Hindu mantra Aum (also called Om). The term omkarasvarupa (Aum is his form), when identified with Ganesha, refers to the notion that he personifies the primal sound. The Ganapati Atharvashirsa attests to this association. Chinmayananda translates the relevant passage as follows:

(O Lord Ganapati!) You are (the Trinity) Brahma, Vishnu, and Mahesa. You are Indra. You are fire [Agni] and air [Vayu]. You are the sun [Surya] and the moon [Candrama]. You are Brahman. You are (the three worlds) Bhuloka [earth], Antariksha-loka [space], and Swargaloka [heaven]. You are Om. (That is to say, You are all this).

Some devotees see similarities between the shape of his body in iconography and the shape of Om in the Devanāgarīand Tamil scripts.

First chakra

As attested to in the Ganapati Atharvashirsa, Ganesha is associated with the first or root chakra (muladhara). Courtright translates this passage as follows:

You continually dwell in the sacral plexus at the base of the spine [muladhara cakra].

Family and consorts

Though Ganesha is popularly held to be the son of Shiva and Parvati, the Puranic myths disagree about his birth. He may be said to be created by Shiva, or by Parvati, or by Shiva and Parvati, or to appear mysteriously and then to be discovered by Shiva and Parvati.

The family includes his brother Skanda, who is also called Karttikeya, Murugan, and other names. Regional differences dictate the order of their births. In northern India, Skanda is generally said to be the elder, while in the south, Ganesha is considered the first born. Skanda was an important martial deity from about 500 BCE to about 600 CE, when worship of him declined significantly in northern India. As Skanda fell, Ganesha rose. Several stories tell of sibling rivalry between the brothers and may reflect sectarian tensions.

Ganesha's marital status, the subject of considerable scholarly review, varies widely in mythological stories. One pattern of myths identifies Ganesha as an unmarried brahmacarin. This view is common in southern India and parts of northern India. Another pattern associates him with the concepts of Buddhi (intellect), Siddhi (spiritual power), and Riddhi (prosperity); these qualities are sometimes personified as goddesses, said to be Ganesha's wives. He also may be shown with a single consort or a nameless servant (Sanskrit: dasi). Another pattern connects Ganesha with the goddess of culture and the arts, Sarasvati or Sarda (particularly in Maharashtra). He is also associated with the goddess of luck and prosperity, Lakshmi. Another pattern, mainly prevalent in the Bengal region, links Ganesha with the banana tree, Kala Bo.

The Shiva Purana says that Ganesha had two sons: Ksema (prosperity) and Labha (profit). In Northern Indian variants of this story, the sons are often said to be Subha (auspiciouness) and Labha. The 1975 Hindi film Jai Santoshi Maa shows Ganesha married to Riddhi and Siddhi and having a daughter named Santoshi Ma, the goddess of satisfaction. This story has no Puranic basis, and Anita Raina Thapan and Lawrence Cohen cite Santoshi Ma's cult as evidence of Ganesha's continuing evolution as a popular deity.

First appearance

Ganesha appeared in his classic form as a clearly-recognizable deity with well-defined iconographic attributes in the early fourth to fifth centuries. Shanti Lal Nagar says that the earliest known cult image of Ganesha is in the niche of the Shiva temple at Bhumra, which has been dated to the Gupta period. His independent cult appeared by about the tenth century. Narain sums up controversy between devotees and academics regarding the development of Ganesha as follows:

What is inscrutable is the somewhat dramatic appearance of Ganesa on the historical scene. His antecedents are not clear. His wide acceptance and popularity, which transcend sectarian and territorial limits, are indeed amazing. On the one hand there is the pious belief of the orthodox devotees in Ganesa's Vedic origins and in the Puranic explanations contained in the confusing, but nonetheless interesting, mythology. On the other hand, there are doubts about the existence of the idea and the icon of this deity" before the fourth to fifth century A.D. ... [I]n my opinion, indeed there is no convincing evidence of the existence of this divinity prior to the fifth century.

Possible influences

Courtright reviews various speculative theories about the early history of Ganesha, including supposed tribal traditions and animal cults, and dismisses all of them in this way:

In this search for a historical origin for Ganesa, some have suggested precise locations outside the Brahmanic tradition.... These historical locations are intriguing to be sure, but the fact remains that they are all speculations, variations on the Dravidian hypothesis, which argues that anything not attested to in the Vedic and Indo-European sources must have come into Brahmanic religion from the Dravidian or aboriginal populations of India as part of the process that produced Hinduism out of the interactions of the Aryan and non-Aryan populations. There is no independent evidence for an elephant cult or a totem; nor is there any archaeological data pointing to a tradition prior to what we can already see in place in the Puranic literature and the iconography of Ganesa.

Thapan's book on the development of Ganesha devotes a chapter to speculations about the role elephants had in early India but concludes that:

Although by the second century AD the elephant-headed yaksa form exists it cannot be presumed to represent Ganapati-Vinayaka. There is no evidence of a deity by this name having an elephant or elephant-headed form at this early stage. Ganapati-Vinayaka had yet to make his debut.

One theory of the origin of Ganesha is that he gradually came to prominence in connection with the four Vinayakas. In Hindu mythology the Vinayakas were a group of four troublesome demons who created obstacles and difficulties but who were easily propitiated. The name Vinayaka is a common name for Ganesha both in the Puranas and in Buddhist Tantras. Krishan is one of the academics who accepts this view, stating flatly of Ganesha, "He is a non-vedic god. His origin is to be traced to the four Vina yakas, evil spirits, of the Manavagrhyasutra (7th–4th century B.C.) who cause various types of evil and suffering".

Depictions of elephant-headed human figures, which some identify with Ganesha, appear in Indian art and coinage as early as the second century BCE.

The title "Leader of the group" (Sanskrit: gaṇapati) occurs twice in the Rig Veda, but in neither case does it refer to the modern Ganesha. The term appears in RV 2.23.1 as a title for Brahmanaspati according to commentators. While this verse doubtless refers to Brahmanaspati, it was later adopted for worship of Ganesha and is still used today. In rejecting any claim that this passage is evidence of Ganesha in the Rig Veda, Ludo Rocher says that it "clearly refers to Brhaspati—who is the deity of the hymn—and Brhaspati only". Equally clearly, the second passage (RV 10.112.9) refers to Indra, who is given the epithet 'gaṇapati', translated "Lord of the companies (of the Maruts)."However, Roucher notes that the more recent Ganapatya literature often quotes the Rigvedic verses to accord Ganesha Vedic respectability.

Two verses in texts belonging to Black Yajurveda, Maitrayaniya Samhita (2.9.1) and Taittiriya Aranyaka (10.1), appeal to a deity as "the tusked one" (Dantih), "elephant-faced" (Hastimukha), and "with a curved trunk" (Vakratunda). These names are suggestive of Ganesha, and the 14th century commentator Sayana explicitly establishes this identification. The description of Dantin, possessing a twisted trunk (vakratunda) and holding a corn-sheaf, a sugar cane, and a club, is so characteristic of the Puranic Ganapati that Heras says, "we cannot resist to accept his full identification with this Vedic Dantin". However, Krishan considers these hymns to be post-Vedic additions. Thapan reports that these passages are "generally considered to have been interpolated", and Dhavalikar says, "the references to the elephant-headed deity in the Maitrayani Samhita have been proven to be very late interpolations, and thus are not very helpful for determining the early formation of the deity".

Ganesha does not appear in Indian epic literature that is dated to the Vedic period. A late interpolation to the epic poem Mahabharata says that the sage Vyasa asked Ganesha to serve as his scribe to transcribe the poem as he dictated it to him. Ganesha agreed but only on condition that Vyasa recite the poem uninterrupted, that is, without pausing. The sage agreed to this but found that to get any rest he needed to recite very complex passages so Ganesha would have to ask for clarifications. The story is not accepted as part of the original text by the editors of the critical edition of the Mahabharata, in which the twenty-line story is relegated to a footnote in an appendix. The story of Ganesha acting as the scribe occurs in 37 of the 59 manuscripts consulted during preparation of the critical edition. Ganesha's association with mental agility and learning is one reason he is shown as scribe for Vyasa's dictation of the Mahabharata in this interpolation. Richard L. Brown dates the story to the eighth century, and Moriz Winternitz concludes that it was known as early as c. 900, but it had not yet been added to the Mahabharata some 150 years later. Winternitz also notes that a distinctive feature in South Indian manuscripts of the Mahabharata is their omission of this Ganesha legend. The term vinayaka is found in some recensions of the Santiparva and Anusasanaparva that are regarded as interpolations. A reference to Vighnakartrinam ("Creator of Obstacles") in Vanaparva is also believed to be an interpolation and does not appear in the critical edition.

Puranic period

Stories about Ganesha often occur in the Puranic corpus. Brown notes while the Puranas "defy precise chronological ordering", the more detailed narratives of Ganesha's life are in the late texts, circa 600–1300. Yuvraj Krishan says that the Puranic myths about the birth of Ganesha and how he acquired an elephant's head are in the later Puranas composed from about 600 onwards and that references to Ganesha in the earlier Puranas such as the Vayu and Brahmanda Puranas are later interpolations made during the seventh to tenth centuries.

In his survey of Ganesha's rise to prominence in Sanskrit literature, Ludo Rocher notes that:

Above all, one cannot help being struck by the fact that the numerous stories surrounding Gaṇeśa concentrate on an unexpectedly limited number of incidents. These incidents are mainly three: his birth and parenthood, his elephant head, and his single tusk. Other incidents are touched on in the texts, but to a far lesser extent.

Ganesha's rise to prominence was codified in the ninth century when he was formally included as one of the five primary deities of Smartism. The ninth-century philosopher Sankaracarya popularized the "worship of the five forms" (pancayatana puja) system among orthodox Brahmins of the Smarta tradition. This worship practice invokes the five deities Ganesha, Vishnu, Shiva, Devi, and Surya. Sankaracarya instituted the tradition primarily to unite the principal deities of these five major sects on an equal status. This formalized the role of Ganesha as a complementary deity.

Beyond India and Hinduism

India had an impact on the regions of western and southeast Asia as a result of commercial and cultural contacts. Ganesha is one of many Hindu deities who reached foreign lands as a result. The worship of Ganesha by Hindus outside of India shows regional variation.

Ganesha was particularly worshipped by traders and merchants, who went out of India for commercial ventures. The period from approximately the tenth century onwards was marked by the development of new networks of exchange, the formation of trade guilds, and a resurgence of money circulation. During this time, Ganesha became the principal deity associated with traders. The earliest inscription invoking Ganesha before any other deity is associated with the merchant community.

Hindus migrated to the Malay Archipelago and took their culture, including Ganesha, with them. Statues of Ganesha are found throughout the Malay Archipelago in great numbers, often beside Shiva sanctuaries. The forms of Ganesha found in Hindu art of Java, Bali, and Borneo show specific regional influences. The gradual spread of Hindu culture to south east Asia established Ganesha in modified forms in Burma, Cambodia, and Thailand. In Indochina, Hinduism and Buddhism were practiced side-by-side, and mutual influences can be seen in the iconography of Ganesha in the region. In Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam, Ganesha was mainly thought of as a remover of obstacles. Even today in Buddhist Thailand, Ganesha is regarded as a remover of obstacles, the god of success.

Before the arrival of Islam, Afghanistan had close cultural ties with India, and the adoration of both Hindu and Buddhist deities was practiced. A few examples of sculptures from the fifth to the seventh centuries have survived, suggesting that the worship of Ganesha was then in vogue in the region.

Ganesha appears in Mahayana Buddhism, not only in the form of the Buddhist god Vinayaka, but also as a Hindu demon form with the same name (Vinayaka).His image appears in Buddhist sculptures during the late Gupta period. As the Buddhist god Vinayaka, he is often shown dancing, a form called Nrtta Ganapati that was popular in northern India, later adopted in Nepal and then in Tibet. In Nepal, the Hindu form of Ganesha known as Heramba is very popular, where he appears with five heads and rides a lion. Tibetan representations of Ganesha show ambivalent views of him. A Tibetan rendering of Ganapati is tshogs bdag. In one Tibetan form, he is shown being trodden under foot by Mahakala, a popular Tibetan deity. Other depictions show him as the Destroyer of Obstacles, sometimes dancing. Ganesha appears in China and Japan in forms that show distinct regional character. In northern China, the earliest known stone statue of Ganesha carries an inscription dated 531 CE. In Japan the Ganesha cult was first mentioned in 806 CE.

The canonical literature of Jainism does not mention the cult of Ganesha. However Ganesha is worshipped by most Jains, for whom he appears to have taken over certain functions of Kubera. Jain connections with the trading community support the idea that Jainism took up Ganesha worship as a result of commercial connections. The earliest known Jain Ganesha statue dates to about the ninth century. A fifteenth century Jain text lists procedures for the installation of Ganapati images. Images of Ganesha appear in the Jain temples of Rajasthan and Gujarat.

Getty, Alice, 1988. The gods of northern Buddhism. Dover Publications Inc. p. 49

Getty, Alice, 2008. Ganesa, a monograph on the elephant-faced God. Pilgrim Publishing. P. 49

Truong, Alain R., 2014. Indian & Southeast Asian Art . http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2014/01/15/28957839.html .