ABS 058

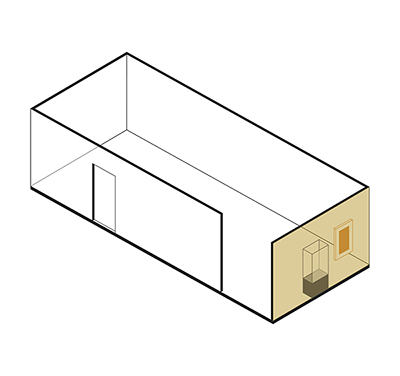

Code: ABS 058

Country: Nepal

Style: Early Malla Period

Date: 1200 - 1300

Dimensions in cm WxHxD: 9.5 x 13.5 x 5.9

Materials: Copper

Copper with some traces of gilt, solid cast in one piece.

The separately cast lotus pedestal is lost.

The jewelled ornaments are inlaid with precious stone, some of which are lost.

The garment is decorated with engraved ornaments.

The four-armed goddess, identified as Prajnaparamita (Tib. Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin ma), is seated in the diamond attitude (vajraparyankasana) on a stand originally mounted upon a lotus pedestal. The principal hands display the “gesture of setting in motion the Wheel of the Law” (dharmacakra-pravartana-mudra). The uplifted right hand originally held a rosary (aksasutra) and the left hand the manuscript (pustaka) of the Astasahastrika Prajnaparamita Sutra. Prajnaparamita is a personification of the Astasahastrika Prajnaparamita Sutra which represents her traditional attribute in the shape of a manuscript.

This image does not match any of the descriptions of the four-armed forms of Prajnaparamita listed in the Sadhanamala (SM 156) or the Nispannayogavali (NSP 21). However the Dharmakosa-samgraha (DKS) contains several sadhanas which correspond with the illustrated image (DKS, fol. 28A, 34B, 37A–37B, 85A).

Perfection of Wisdom -

"Perfection of Wisdom" is a translation of the Sanskrit term prajna paramita (Devanagari:

Tibetan: Shes-rab-pha-rol-phyin

Chinese: Pinyin: ban'ruo-boluomìduo

Japanese: hannya-haramitta, hannya-haramitta?)

Korean: banya-paramilda

Vietnamese: Bat Nha Ba La Mat Da)

- which is one of the aspects of a bodhisattva's personality called the paramitas.

The Perfection of Wisdom Sutras or Prajnaparamita Sutras are a genre of Mahayana Buddhist scriptures dealing with the subject of the Perfection of Wisdom. The term Prajnaparamita alone never refers to a specific text, but always to the class of literature.

History

The earliest sutra in this class is the Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita Sutra or "Perfection of Wisdom in 8,000 Lines", which was probably put in writing about 100 BC and is one of the earliest Mahayana sutras. More material was gradually compiled over the next two centuries. As well as the sutra itself, there is a summary in verse, the Ratnagunasamcaya Gatha, which some believe to be slightly older because it is not written in standard literary Sanskrit.

Between the years 100 and 300 this text was expanded into large versions in 10,000, 18,000, 25,000 and 100,000 lines, collectively known at the "Large Perfection of Wisdom". These differ mainly in the extent to which the many lists are either abbreviated or written out in full; the rest of the text is mostly unchanged between the different versions.

Since the large versions proved to be unwieldy, they were later summarized into shorter versions, produced from 300 to 500. The shorter versions include the Heart Sutra (Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya Sūtra) and the Diamond Sutra (Prajñāpāramitā Vajracchedikā Sūtra). These two are widely popular and have had a great influence on the development of Mahayana Buddhism.

Tantric versions of the Prajnaparamita literature were produced from 500 on. The Prajnaparamita terma teachings are held to have been conferred upon Nagarjuna by Nagaraja, the King of the nagas, who had been guarding them at the bottom of a lake.

Teachings

"At first sight, The Perfection of Wisdom is bewildering, full of paradox and apparent irrationality. Yet once one accepts that trying to unravel these texts without experiencing the intuitions behind them is not satisfactory, it becomes clear that paradox and irrationality are the only means of conveying to the reader those underlying intuitions that would otherwise be impossible to express. Edward Conze succinctly summarized what The Perfection of Wisdom is about, saying, 'The thousands of lines of the Prajñāparamitā can be summed up in the following two sentences:

1. One should become a bodhisattva (or, Buddha-to-be), i.e. one who is content with nothing less than all-knowledge attained through the perfection of wisdom for the sake of all beings.

2. There is no such thing as a bodhisattva, or as all-knowledge, or as a 'being', or as the perfection of wisdom, or as an attainment. To accept both of these contradictory facts is to be perfect.'

The central idea of The Perfection of Wisdom is complete release from the world of existence. The Perfection of Wisdom goes beyond earlier Buddhist teaching that focused on the rise and fall of phenomena to state that there is no such rise and fall — because all phenomena are essentially void.

The earlier perception had been that reality is composed of a multiplicity of things. The Perfection of Wisdom states that there is no multiplicity: all is one. Even existence (samsara) and nirvana are essentially the same, and both are ultimately void. The view of The Perfection of Wisdom is that words and analysis have a practical application in that they are necessary for us to function in this world but, ultimately, nothing can be predicated about anything.

Within this context of voidness, The Perfection of Wisdom offers a way to enlightenment. It represents the formal introduction to Buddhist thought of a practical ideal — the ideal of a bodhisattva. Unlike an arhat or pratyekabuddha, beings who achieve enlightenment but cannot pass on the means of enlightenment to others, a bodhisattva should and does teach. A bodhisattva must practice the six perfections: giving, morality, patience, vigour, contemplation and wisdom. Wisdom is the most important of these because it dispels the darkness of sensory delusion and allows things to be seen as they really are."

R.C. Jamieson: The Perfection of Wisdom (New York: Penguin Viking, 2000. ISBN 0-670-88934-2 pp. 8–9)

For example, the Diamond Sutra concludes with:

As stars, a fault of vision, a lamp,

A mock show, dew drops, or a bubble,

A dream, a lightning flash, or a cloud,

So should one view what is conditioned.

Stars cannot be grasped. Things seen with faulty vision do not really exist. Lamps only burn as long as they have fuel. A mock show is a magical illusion; it is not as it seems. Dew drops evaporate quickly in the heat of the sun. Bubbles are short lived and have no real substance to them. Dreams are not real, even though they may seem so at the time. Lightning is short lived and quickly over. Clouds are always changing shape. By realising the transient nature of things, it is easier to detach from them and to attain Nirvana.

Bhattacharyya, Benoytosh , 1958. Indian Buddhist Iconography. Calcutta: K. L. Mukhopadhyay. Pp. 197–99, 326 - References to the iconography of Prajnaparamita

Bhattacharyya, Dipak Chandra, 1974. Tantric Buddhist Iconographic Sources. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. Pp. 33-34 - References to the iconography of Prajnaparamita

Bhattacharyya, Dipak Chandra, 1978. Studies in Buddhist Iconography. New Delhi: Manohar. Pp. 29-67 - References to the iconography of Prajnaparamita

Bock, Etienne; Falcombello, Jean-Marc; Jenny Magali, 2022. Trésors du Tibet. Sur les pas de Milarépa.. Paris: Flammarion. P. 186-187

Chandra, Lokesh, 1986. Buddhist Iconography of Tibet (CBIT). Rinsen Book Co.. Nos. 46, 699, 700, 954, 1083, 2361 (158) - References to the iconography of Prajnaparamita

Conzé, E, 1949. "The Iconography of Prajnaparamita - I". OA, Vol.II. Pp. 47–52, 5 figs - References to the iconography of Prajnaparamita

Conzé, E., 1951. "The Iconography of Prajnaparamita - II", OA, Vol.III, No. 3. OA, Vol.III, No. 3. Pp. 104–9, 6 figs - References to the iconography of Prajnaparamita

de Mallmann, Marie-Thérèse, 1975. Introduction à l'iconographie du tântrisme bouddhique. Paris: Adrien Mainsonneuve (Jean Maisonneuve successeur (1970). Pp. 305-307 - References to the iconography of Prajnaparamita

Jamieson, R. C., 2000. The Perfection of Wisdom . New York : Penguin Viking. pp. 8–9

Sèngué, Tcheuky, 2002. Petite Encyclopédie des Divinités et symboles du Bouddhisme Tibétain. Editions Claire Lumiere . Pp. 332-333